Even as Chennai is again in the spotlight for its severe water crisis, an analysis of its civic history reveals that the city has often preyed upon its neighbourhood for meeting its never-ending demand for water.

Groundwater is the lifeline of the city and its neighbouring areas. The official water is sourced from water wells.

Chennai has over 0.42 million wells according to Excreta Matters, 2012, a research by Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment. Of these, only 27,000 are open wells, which extract 150 million litres per day (MLD) of groundwater — with the average rate of extraction at about 400 litres per well per day says the study.

Over and above this, around 66 per cent of households in the city have their own private wells. This has led to a general fall in water levels as well as a decline in average yields per well.

Between 1991 and 2002, groundwater levels fell at a rate of a little less than one metre a year; between 1999 and 2004, the level fell at a faster rate of close to two metres a year. The study also adds that there has been an increase in the number of borewells and many open wells have dried up.

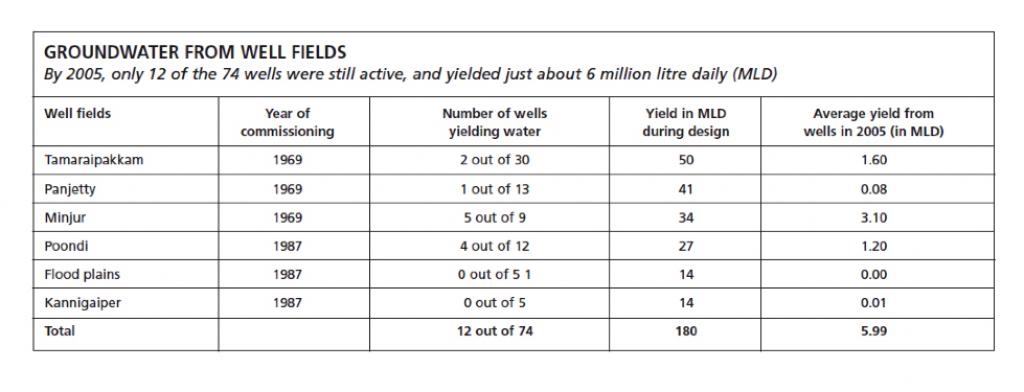

Source: Excreta Matters, 2012, Centre for Science and Environment

Chennai’s water wars

The city has tried to bring forth several legislations to save its groundwater. The first of these was the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Act, 1978.

But these laws did not help, according to S Janakrajan of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS) in his 2007 paper titled Strengthened city, marginalised peri-urban villages: Stakeholder dialogues for inclusive urbanisation in Chennai, India.

He explained that in spite of the Acts, water scarcity increased in leaps and bounds. The Chennai Metro Water Board had resorted to extracting water from the peri-urban villages of the city.

Thus, the Acts were violated by the government agency as well as individual residents, who moved towards groundwater use to compensate the water shortage.

According to a 2018 research paper published in the journal World Development, Chennai Metro Water Board strategised the purchasing of riparian water permits.

The Board bought the riparian rights in neighbouring Tiruvallur and Kancheepuram districts as early as the 1960s.

However, given the shared nature of groundwater aquifers and the continued dependence of many small and marginal farmers, who drew water from these aquifers for agriculture, the strategy had led to significant tensions between rural communities and Chennai, and among rural communities themselves.

“On one hand, enterprising farmers have converted their riparian rights into a profitable water trade, but on the other, many others have been negatively affected, producing conflict both within rural communities and between rural communities and Chennai,” the research explains.

Related Stories

According to surveys conducted in the Magaral and Palayaseevaram villages, agricultural production had been negatively affected by excessive groundwater extraction on the part of the Chennai Metro Water Board, adds the study.

CSE’s 2012 research talks about the village of Velliyur, 50 kilometres from Chennai, in the basin of the Araniyar-Kortallaiyar rivers, where groundwater extraction was started as early as 1969 by the Board. About 11 borewells were installed to pump water from the village common lands to supply 16 MLD to nearby industries and Chennai city.

By 2000, nine borewells had failed. Chennai Metro Water Board then signed up 75 farmers to source 40 MLD. But by 2004, the water supply from the wells had declined to 17 MLD and more wells were going dry.

Violence

As water stress grew, tension over withdrawal also rose. People wanted the local panchayat to issue orders banning the export of water from the village.

The council declined. When aggrieved farmers went to court and got a stay on the sale of water, Metro Water intervened and supported those farmers who were selling water.

Agricultural output declined and the people had no option but move to sand mining in the riverbed. But this had an adverse impact on water recharge and soon, the water-selling farmers protested.

Metro Water used its influence to ban sand mining. By August 2004, tensions had reached a flashpoint and violence broke out as people stormed the local Metro Water office. To buy peace, it was agreed that water sale would be stopped within a month.

But this promise was not kept, as the powerful lobby of water-sellers and city officials obtained a stay from the court on the settlement. The conflict grew. By mid-September 2004, the entire village came together to block the roads and in the ensuing agitation, public pipelines were damaged.

People were arrested. A case was filed. The court asked the villagers to compensate Metro Water. This left the people protesting against the water withdrawal dispirited and dejected. Water sales started again. Metro Water even put up a notice soliciting water from farmers.

This year, according to news reports, the aquifer along Tiruvallur has dried up and the Board has moved towards the Thamaraipakkam area in Tiruvallur district which is considered rich in groundwater.

The urban water needs have won over the rural rights. It is now time to look into the implementation of the Acts once again, say the experts.

Legislations to save Chennai’s groundwater reserve

1978: The Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Act, 1978, was introduced. This was done to promote and secure the planned development of water supply and sewerage services.

It also had the mandate to ensure the efficient operation, maintenance and regulation of the water supply and sewerage systems in the Chennai Metropolitan Area and prepare immediate and long-term measures to meet future demands for water and sewerage services in the Chennai Metropolitan Area.

1987: The city of Chennai was the first in India to legislate for urban groundwater through the Chennai Metropoliton Area Groundwater (Regulation) Act. The notified area under this Act includes the entire city of Chennai and 302 villages surrounding the city.

The Act envisaged the control, regulation, abstraction and transportation of groundwater in the notified area through the registration of existing wells, issuing licenses to extract water for non-domestic use and to transport groundwater on vehicles. The Act exempted wells used for agricultural purposes from its purview.

2002: The state tightened these rules by promulgating the Chennai Metropolitan Area Groundwater (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2002.

2003: The Tamil Nadu Groundwater (Development and Management) Ordinance, 2003 was passed. Under it, transporting water from notified areas without permission became a strict no-no. The ordinance established a Tamil Nadu Ground Water Authority to oversee these regulations.